|

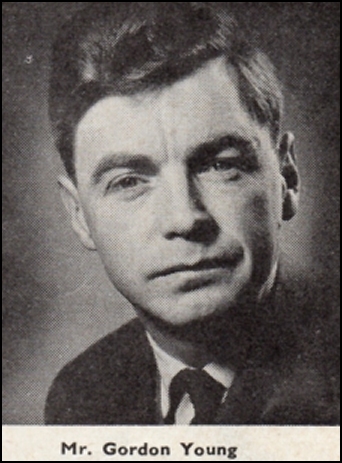

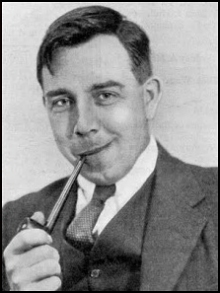

| The recollections of Gordon Young, the First Mate

on the 'Laloun' |

| |

| Let me start by telling you that I joined the

Company in 1946. Before that, I joined the Royal Navy, signing up at 17

(1942), did my time on the Lower Deck serving in a Mine Layer as a very

‘ordinary ’seaman, doing sea time to qualify for Officer Training,

commissioned as a Midshipman (1943) served on a LCT and was at the

Normandy Landings in June 1944. Then had a spell ashore to qualify in

Navigation and Watch Keeping and was posted to an Escort Carrier and

spent most of the rest of the war in the Far East and was at Singapore

for the surrender of the Japanese. By this time I had got my first

stripe and was now Sub Lieut. W G Young RNVR. |

| |

| I was due to be ‘demobbed’ in the October of

1946 and spent the last three months at a Shore Base in Scotland where I

met Lieut. Commander Saunders RNR and that is when my career with Pan

started. |

| |

|

|

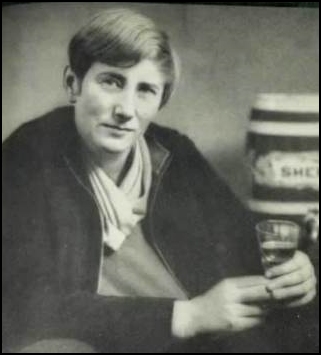

Gordon with Commander Saunders |

| |

| Saunders had been a deep sea trawler skipper

before the war and was also a very competent marine engineer and he had

been approached by Pan to take on the skipper of Laloun and was looking

for a ‘No.1’ to handle the Navigation and deck work and he invited me to

join him. As I had no idea what I was going to do when I came out of the

Navy (having been turned down for a permanent career with the Royal

Navy) I jumped at this opportunity not knowing exactly what I was

letting myself in for. It was only later when I met my new bosses Alan

Bott and Aubrey Forshaw that I learnt of their intentions to print in

France and bring the books back to the UK in their own boat.

|

| |

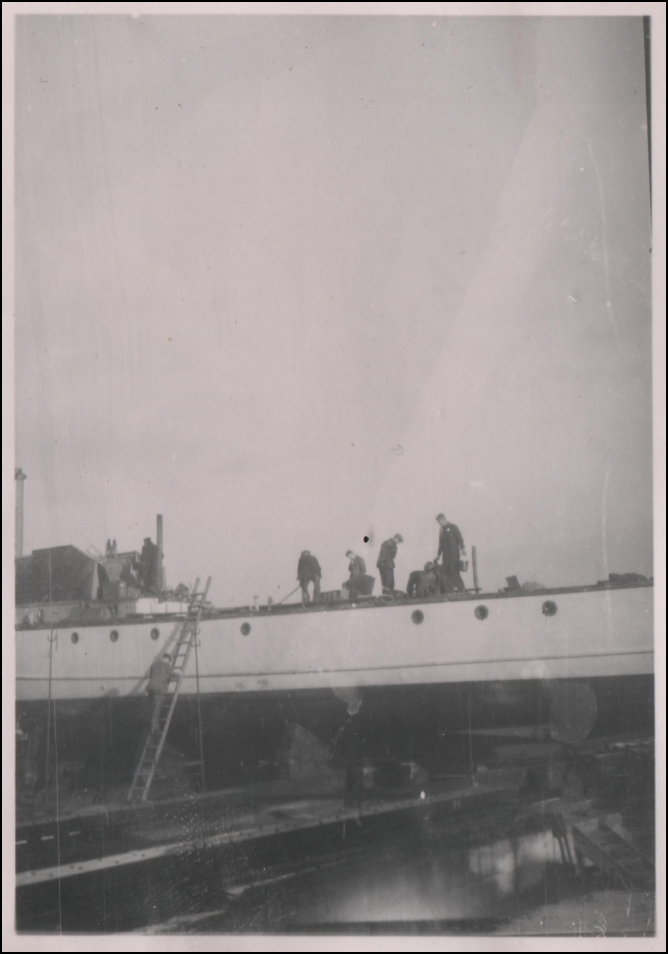

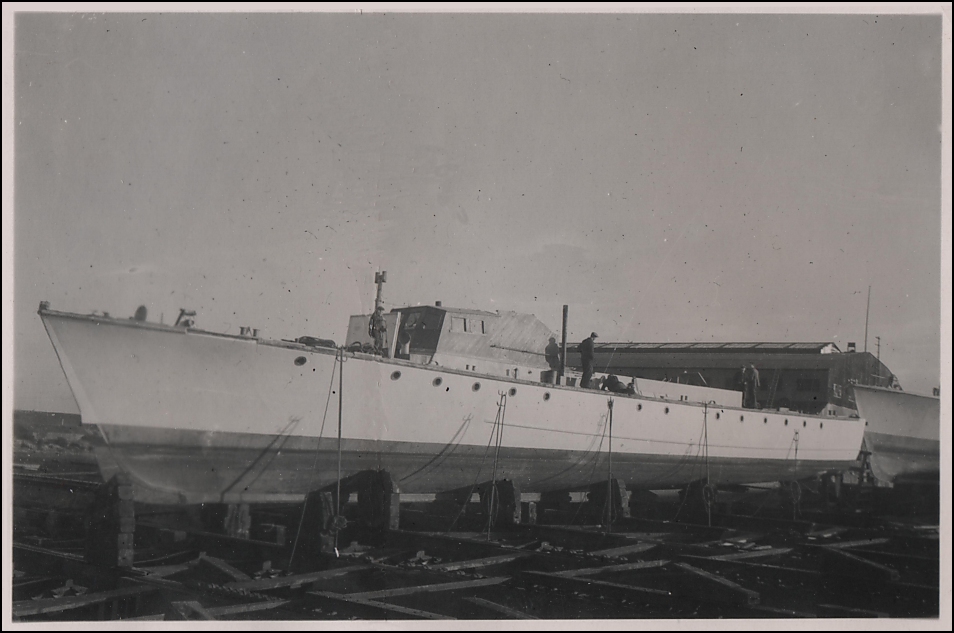

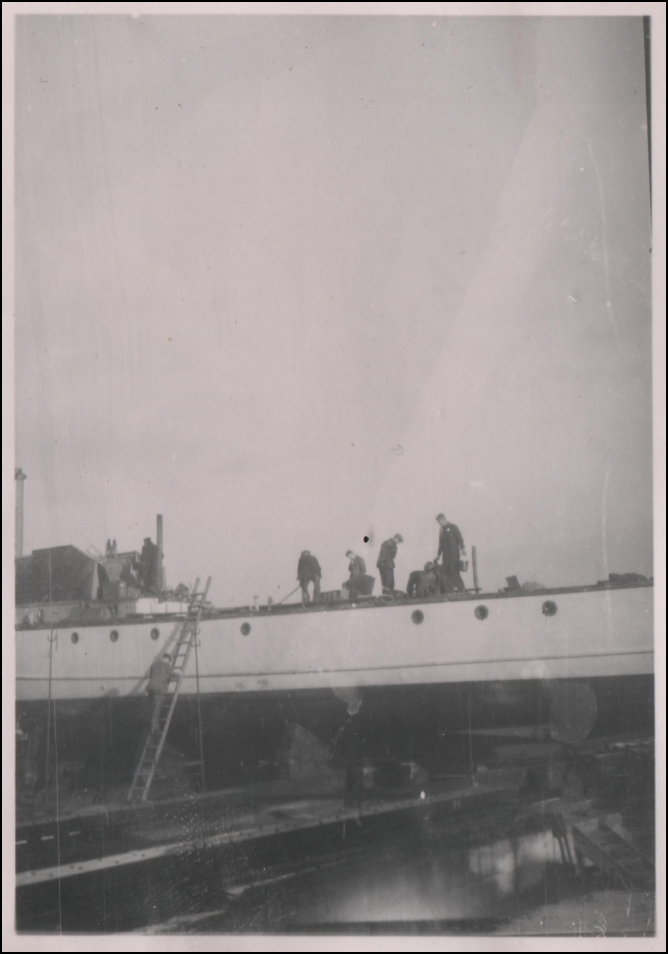

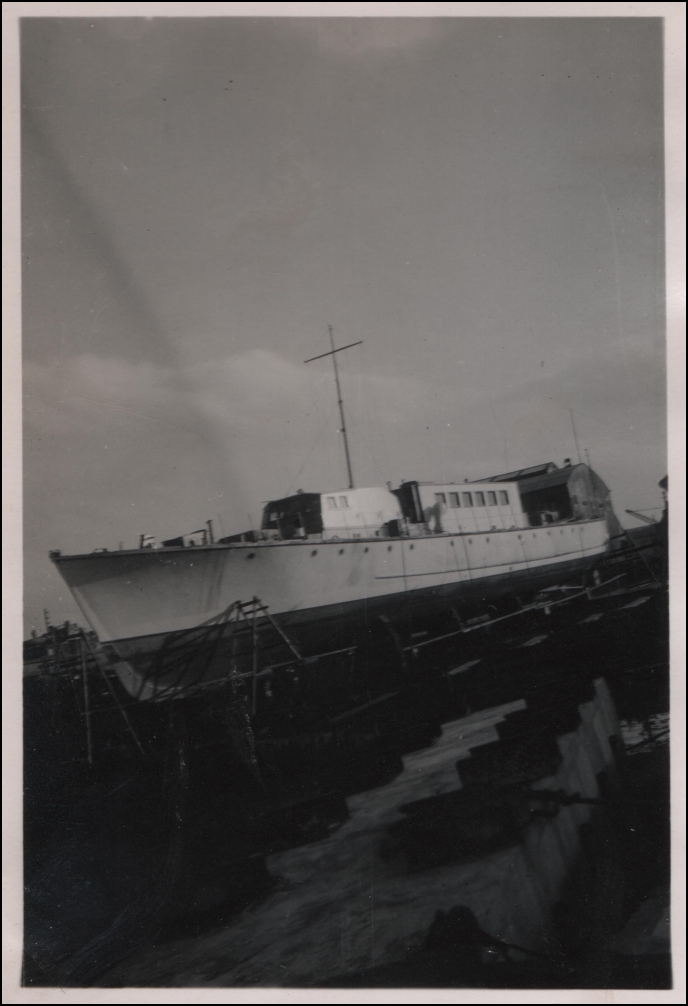

| So in October 1946 I came out of the Navy,

went down to London, met my new employers, who sent me back up to

Scotland to Peterhead where a ’new boat’ was lying. This turned out to

be a brand new 110ft Fairmile Motor Launch, built locally, which had

been purchased from the Admiralty - it was just a bare hull – no

engines. The London Office had arranged for a boat yard (Thorntons) in

Inverness to take on the job of the conversion to carry cargo (books).

It was towed from Peterhead to Inverness with me on board and work

started in the November and continued throughout the Winter of 1946/47 –

the coldest Winter on record in Scotland at that time. Skipper Saunders

joined me and we lived aboard most of the time to supervise the work. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

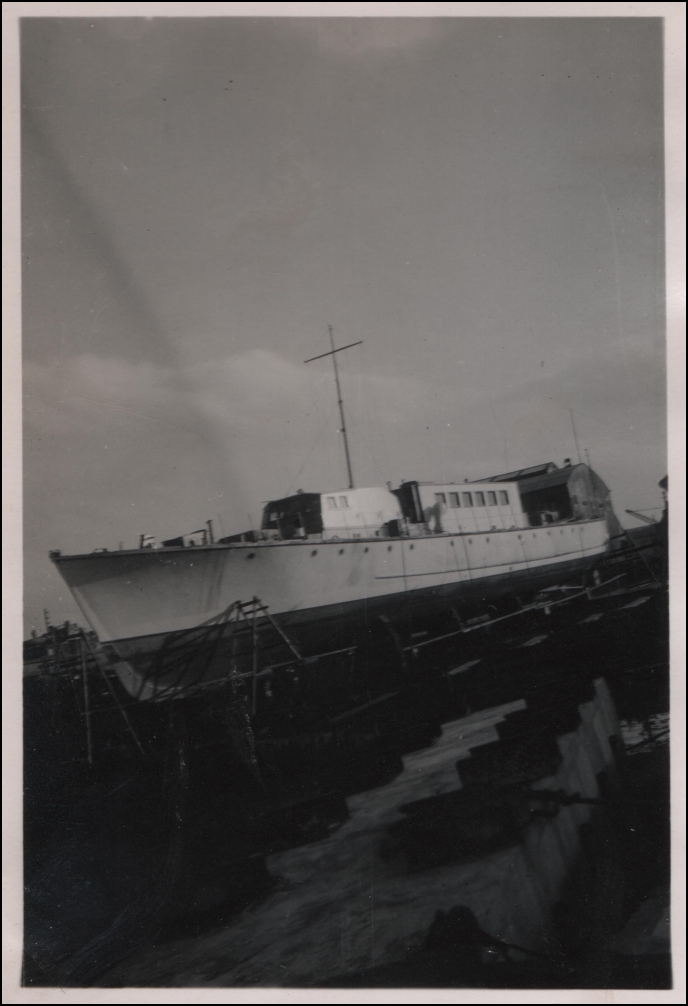

Working on the 'Laloun' at Inverness |

| |

| Work was completed by May 1947 and with two

local lads as Crew we came South, met our bosses who thoroughly approved

of the ship and after giving them a short trip up the Thames, we

prepared for our first voyage to Paris – down the Thames, across the

Channel and up the Seine to Paris. And that was how it all started. |

| |

|

| The 'Laloun' at Kingston Upon Thames wharf. |

| |

| The ship was named ‘Laloun’ from Kipling’s

‘On a City Wall’. Alan Bott had the book on his desk when he was

deciding a name. All ship’s names are registered at Lloyds and no two

or more ships can have the same name. Originally AB ( as Alan Bott was

always known) wanted the name ‘Patricia’ but that wasn’t possible as it

was already in use. Also there was a ship using the name ‘Lalun’ so he

just added the ‘o’ and so MV ‘Laloun’ became its registered name. |

| |

| Before continuing the

story of MV 'Laloun', let me back track and briefly explain how it all

began. You will probably know, but if you don’t, what I have to

tell you now is all part of the story. When the Company first

decided to publish paperbacks, to be known as Pan Books, they could not

get paper to print in the UK. Immediately after the war, paper was

still in short supply and rationed to existing publishers. But

there was plenty of paper in France and the then Board of Trade gave

permission for the books to be printed at two printers in Paris and the

idea of the boat was considered. Interestingly the idea came from

a close friend of Alan Bott (AB) and Aubrey Forshaw (ADF), named Edward

Young ( no connection with me! ). He had been a director of the

book design company ‘Rainbird Maclean’ and his interests were looked after

by AB/ADF during the war while he served in the Royal Navy. He was

a pre-war RNVR officer and was one of very few RNVR officers to achieve

command of a submarine and served with distinction. He made the

suggestion for Pan to have its own boat to bring the books back from

Paris as the most economical way.

|

| |

| So in June 1947, we made

our first trip to Paris. The Seine, of course, like so many of the

rivers on the Continent, has always been used by commercial barge

traffic and the Seine was a busy waterway, and I believe at that time we

were the only UK registered ship sailing to Paris. We had

organised a mooring on the Thames at Kingston upon Thames, being the

nearest to the warehouse at Esher. The London Office had rented an

old wartime parachute packing shed for its first warehouse.

|

| |

|

| |

| We would leave Kingston on a Monday

(this would be our pattern for most of our future sailings) down the

Thames, lock through at Teddington into the Thames tideway, passing

under the London bridges (a bit scary to start with) then on down to

Tilbury where we picked up a pilot who took us down the Thames Estuary,

round North Foreland, passing Deal and Dover and dropping the pilot off

Dungeness. We then crossed the Channel, fetching up at Le Havre on the

Tuesday evening where we stayed overnight and proceeded into the Seine

via a canal from Le Havre docks. This avoided the very treacherous

approach via the Seine estuary. Then on to Rouen to pick up a river

pilot (compulsory) to take us up river to Paris, a distance of some 90

miles. |

| |

| The journey to Paris usually took two days –

there were 8 locks to negotiate between Rouen and Paris, the Seine at

Paris being some 90ft above sea level – and very often we had to wait

our turn. The locks are vast comprising two locks – le petit ecluse (for

a single vessel with priority) and le grande ecluse which could take 6

or 8 large barges all operated by lock keepers. With our French pilot

(Maurice) who knew all the lock keepers and with a judicious ‘tip’ (pour

boire !) we usually managed to get through quite quickly. We could not

travel at night so the journey time to Paris varied between 2 and 3

days. We always aimed to arrive in Paris on a Friday. This gave us the

weekend before loading on the Monday. |

| |

| Aubrey Forshaw,(ADF) who I was to learn later

started life at 14 years of age as a ‘printers devil’ (If you don’t know

what a ‘printers devil’ is, ask me) and also was a keen ‘Francophile and

knew Paris well. as I was to discover later. One of his many friends in

the French publishing world, was one, Robert Mouzillat, (RM) and it was

he who met us on arrival in Paris. RM had been responsible for arranging

with two French printers in Paris to print the first Pan Books that we

were to bring back to the UK. He also made arrangements for us to be

moored, for the weekend alongside the Touring Club de France floating

club house, just close to the Pont de la Concorde. This became or

regular arrangement on every trip. Mooring alongside the TCF floating

club house, enabled us to top up with fresh water and connect with their

electricity supply. All very convenient. |

| |

|

| Moored up at the Touring Club de France |

| |

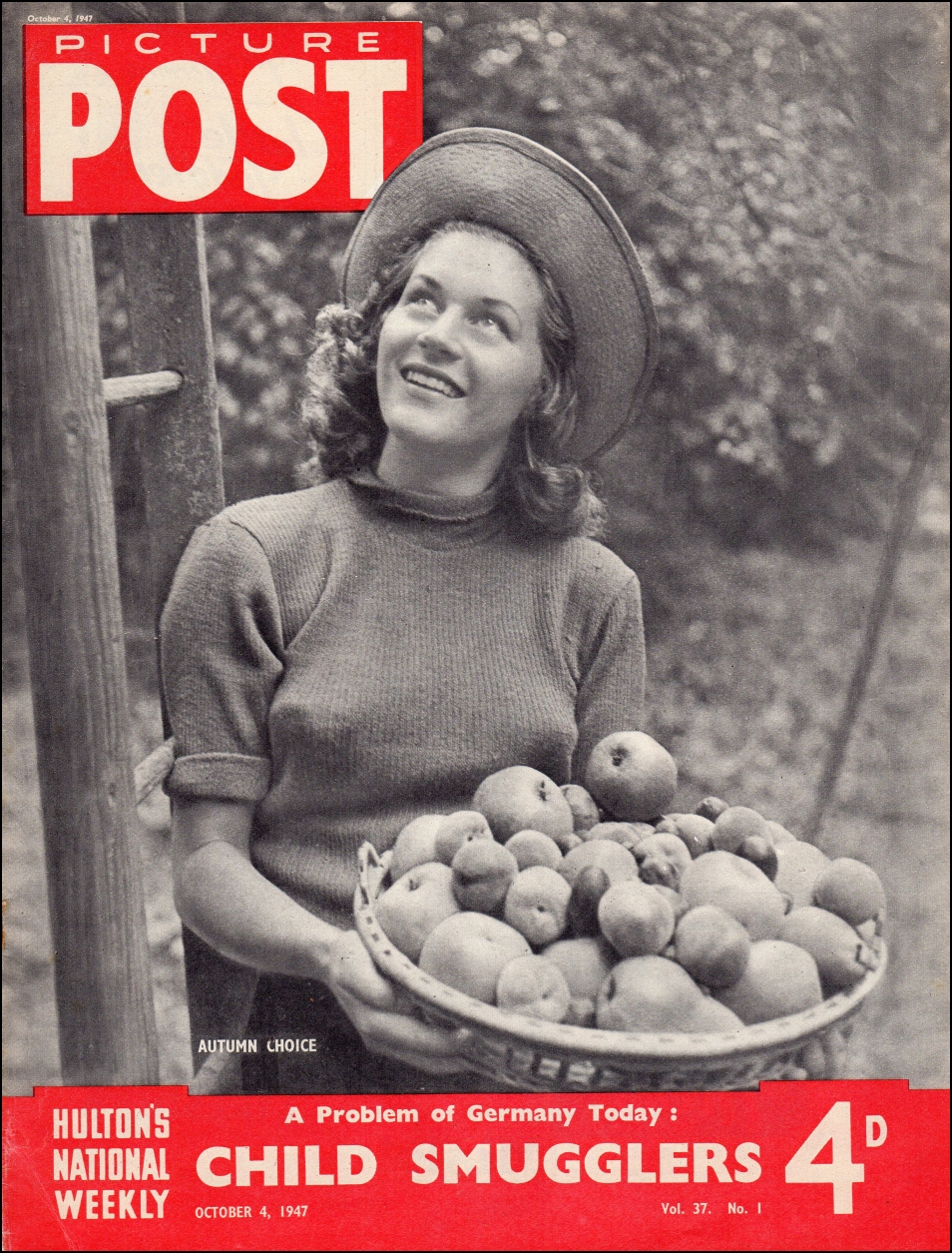

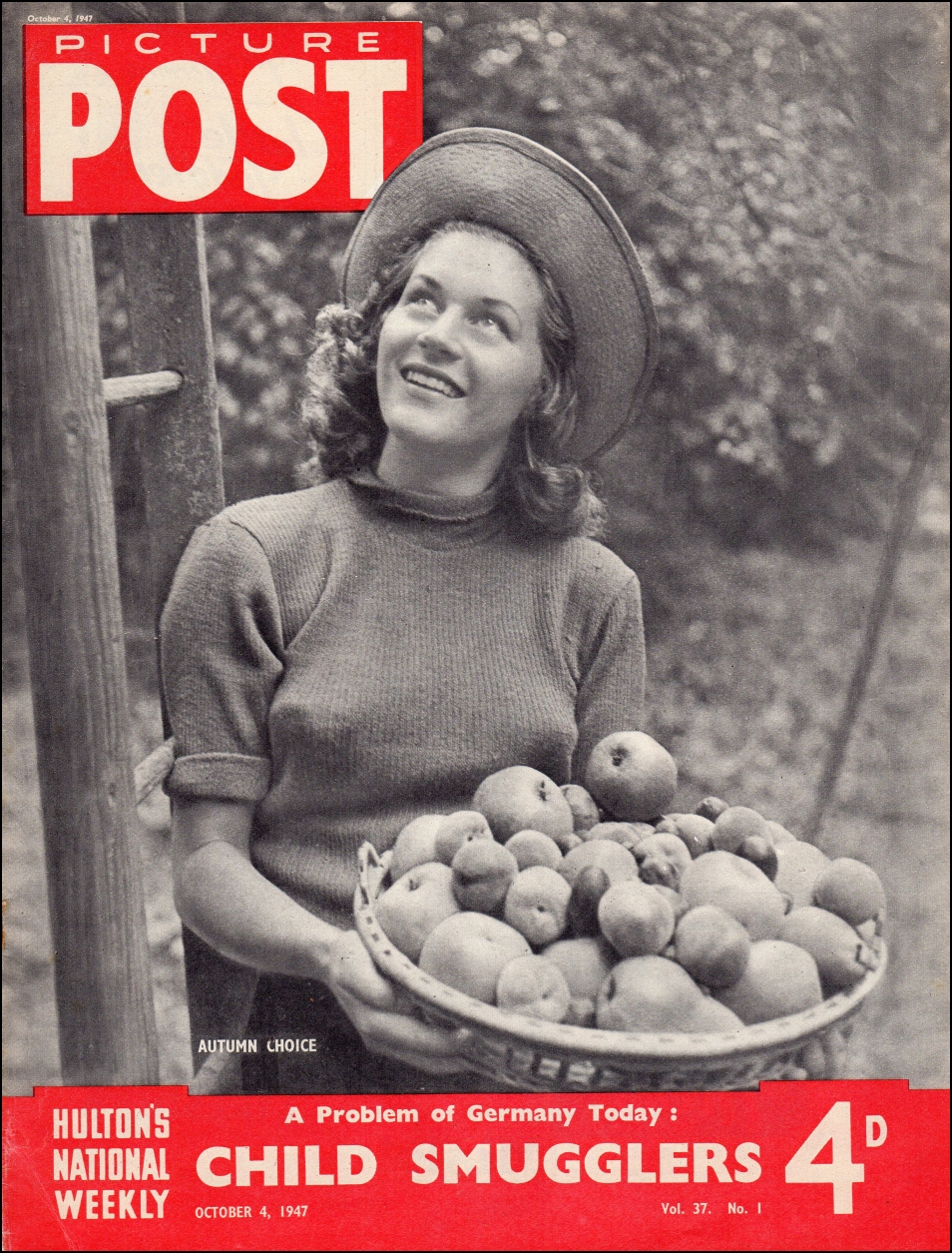

| 'Picture Post' was interested in the story

and sent reporter Merlyn Severn on the first trip. |

| |

|

| |

| Let me tell you about Merlyn Severn. This is

what she told me... She had been a wartime photo-journalist for 'Picture

Post' and although never allowed up at the frontline, she had followed

the British advance all through France and into Germany, photographing

the carnage and destruction. However, I met her on the quayside at

Kingston on Thames one Sunday afternoon in September 1947. We were due

to sail the following morning and I was the only one aboard, relaxing

after unloading the previous day. The skipper and our two crew were due

back later. I heard a very ‘mannish’ voice hail the ship and going on

deck was confronted by this rather round, five foot nothing ‘person’

strung around with cameras, light meters and all the trappings of her

trade. She had to cross a narrow gangplank to get aboard which she

managed with my help holding her hand. I knew we were expecting someone

from Picture Post but was not expecting a ‘lady’ She admitted she was

really hitching a lift to Paris where she had another assignment but she

certainly worked her passage and you can now see the result of her

‘story’ |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

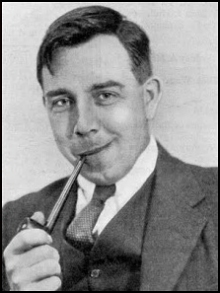

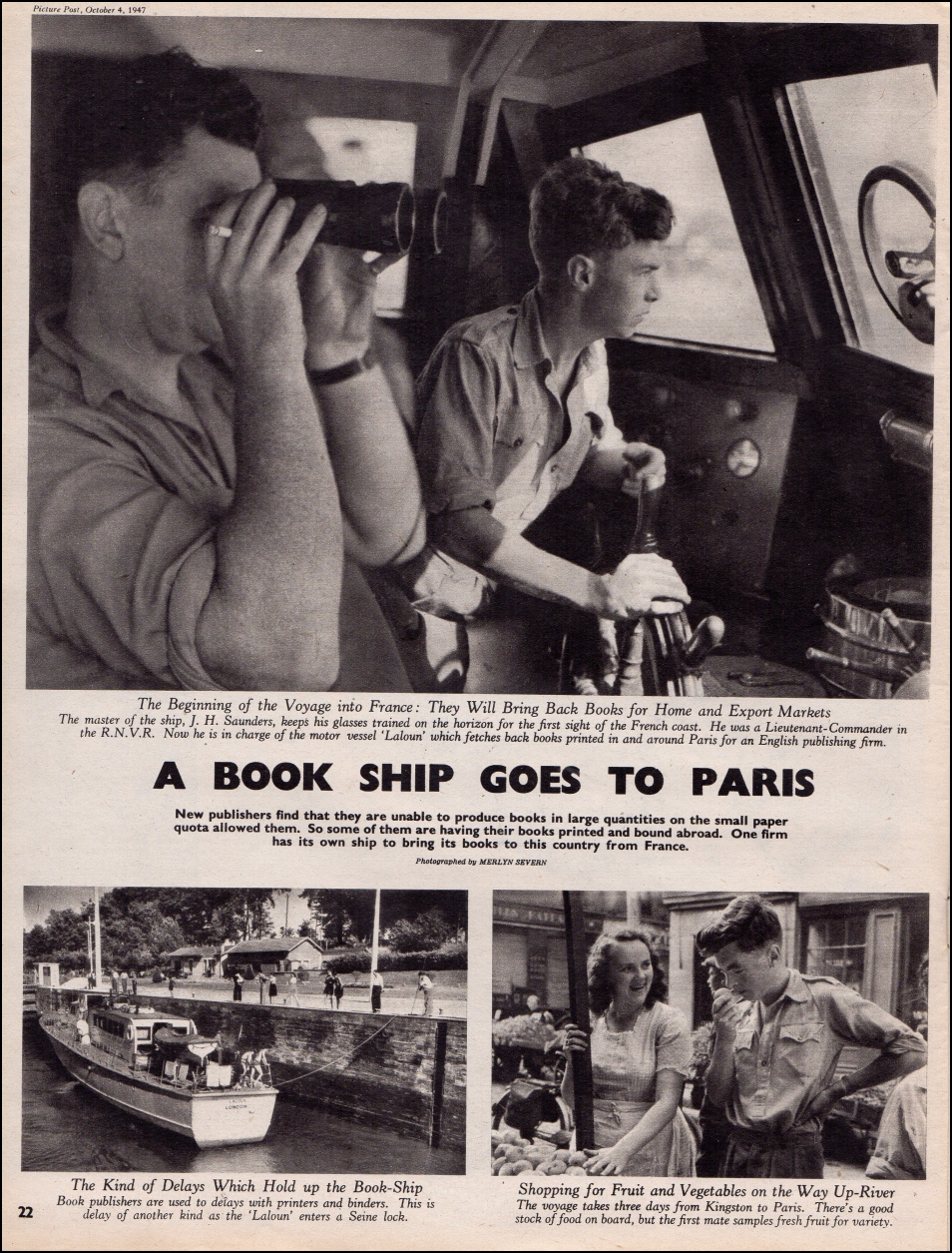

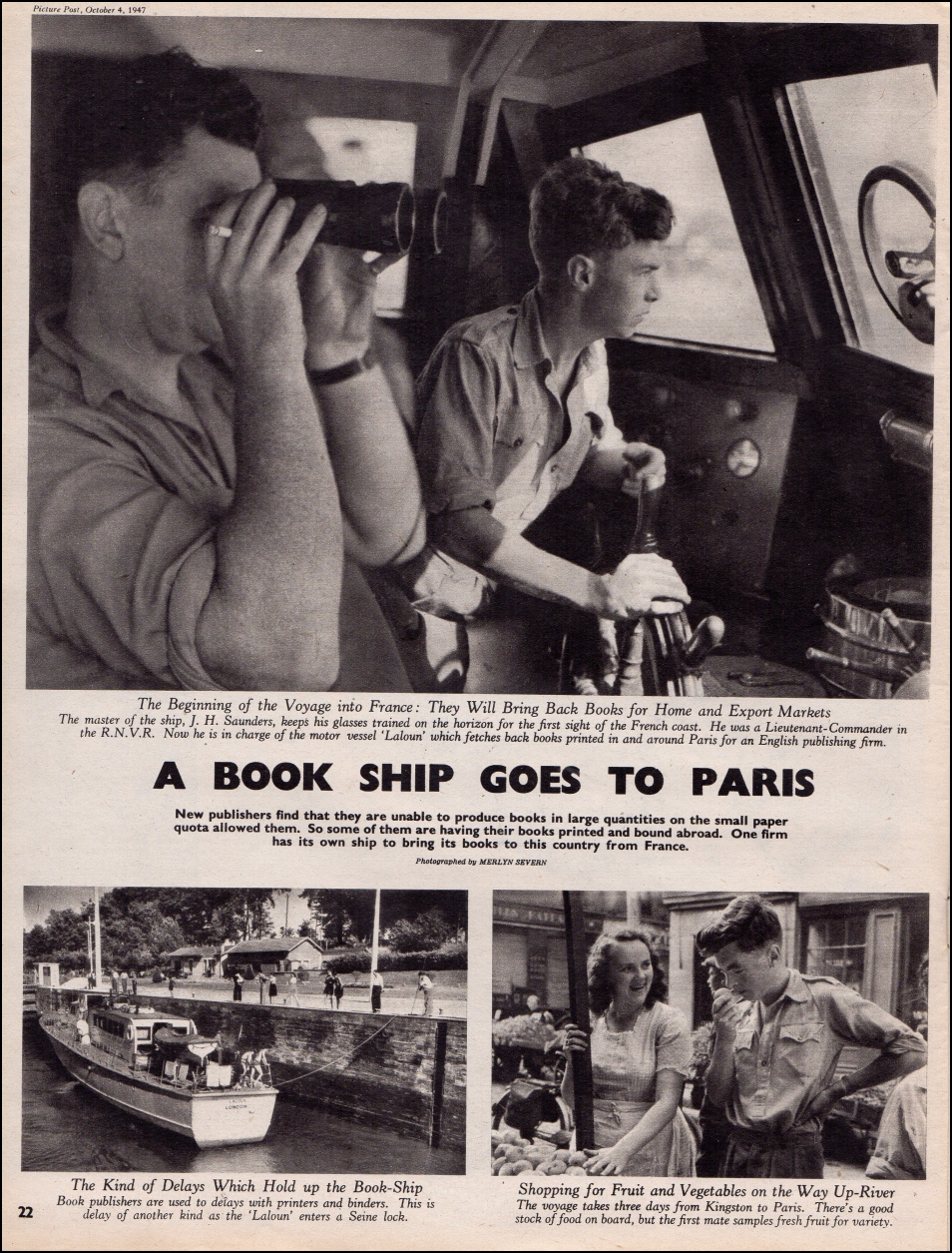

| Let me take the main picture of Skipper

Saunders and 1st Mate Gordon Young first. The caption below the picture

states.....”J H Saunders keeps his glasses trained on the horizon for

the first sight of the French coast”..sounds very dramatic but In fact

we were still on the lower reaches of the Thames – the picture was taken

through the wheelhouse window and if you look closely at the window

behind my head, you can see some smudges – that was the shore – erased

by clever photography (but not quite) So thoroughly posed ! Saunders was

on the run from his wife and the binoculars were supposed to hide his

face. His right hand holding the cigarette shows a foreshortened 4th

finger. He had lost the tip of his finger some years previous. That was

a giveaway for his wife to track him down some time later. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

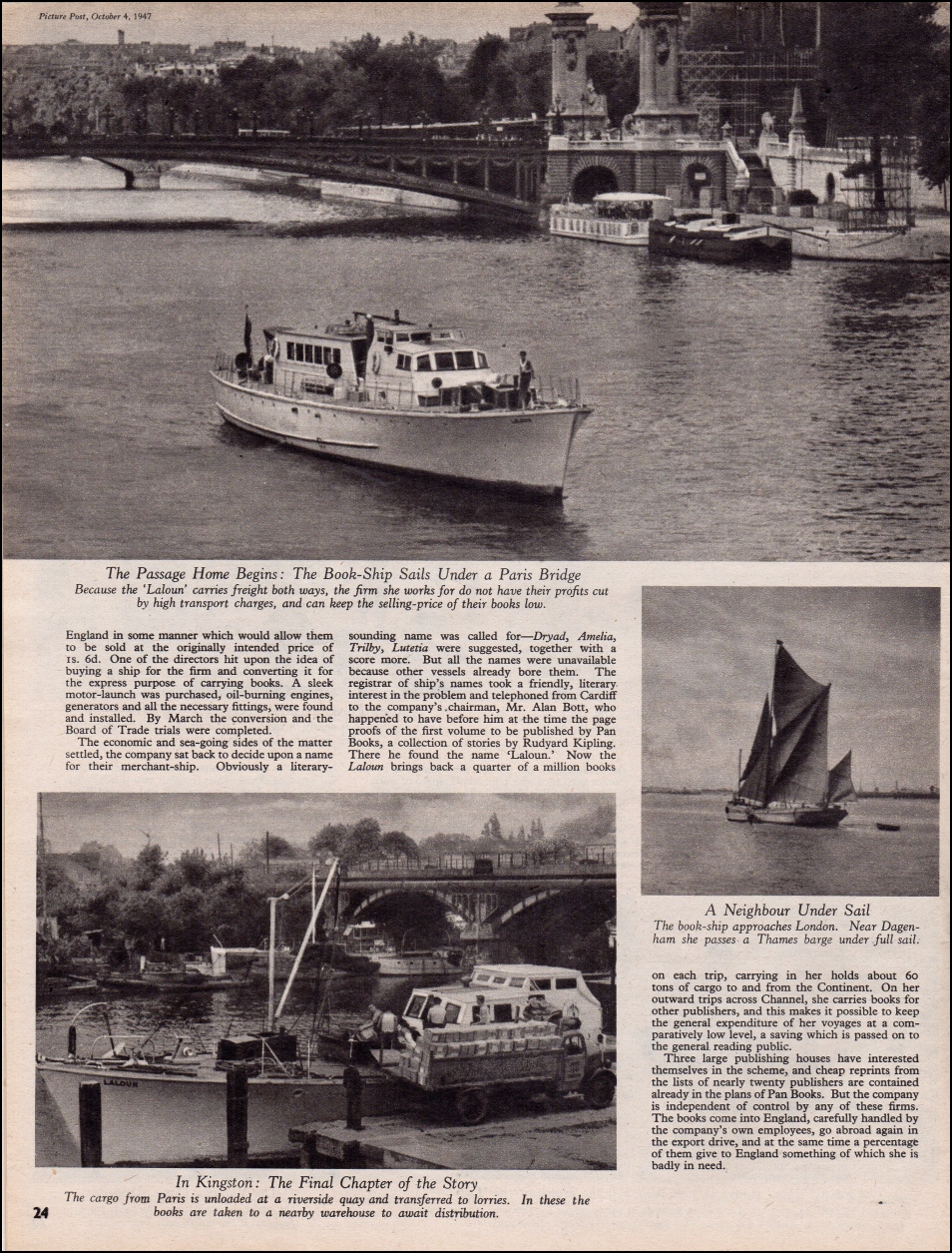

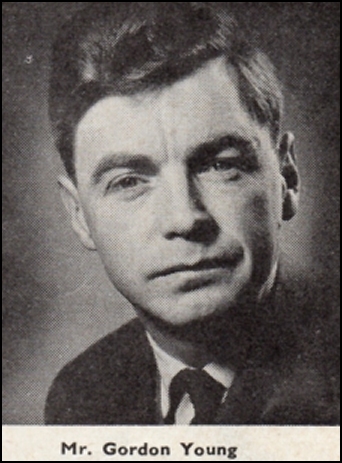

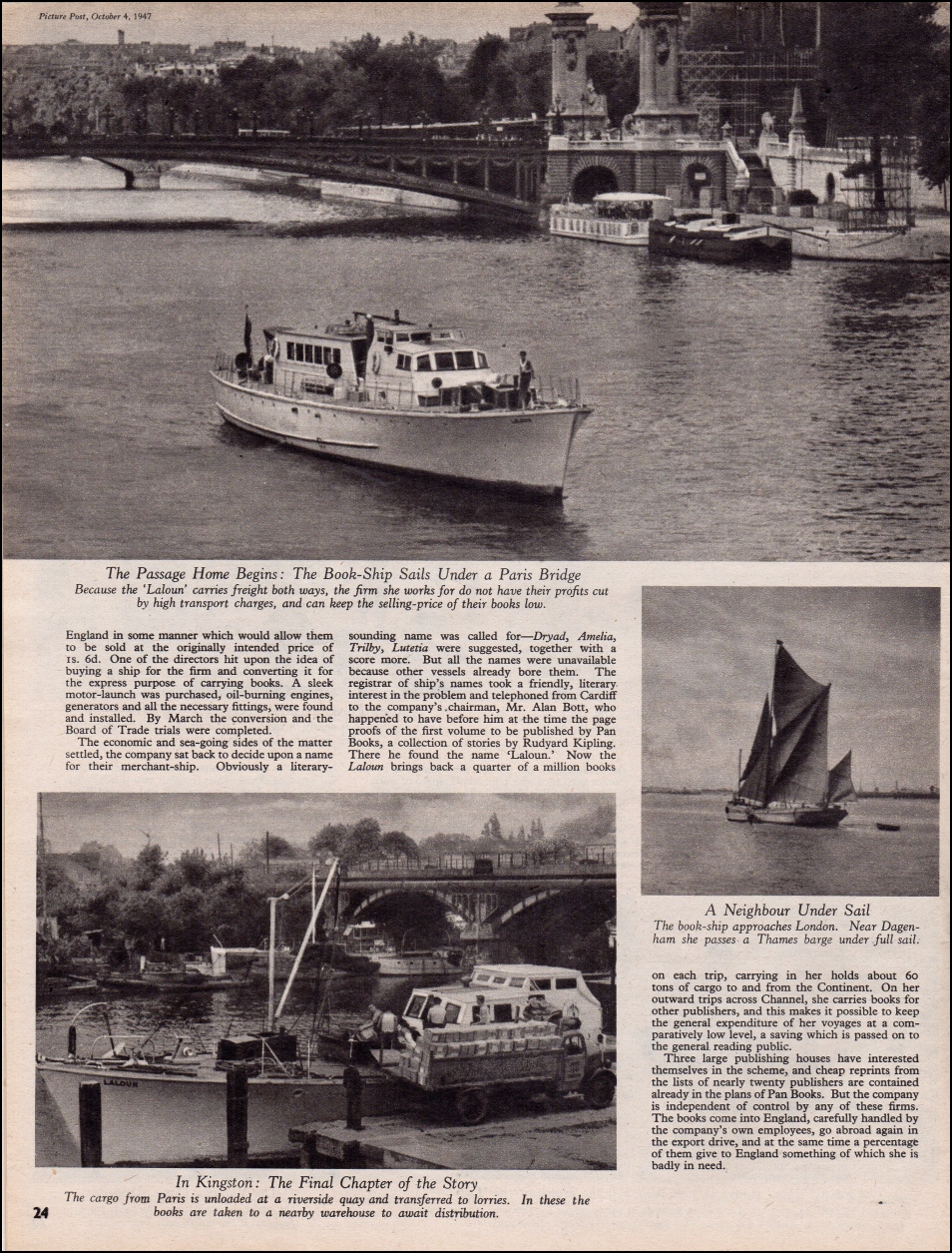

| The other picture of 'Laloun' on the Seine

with the caption... “The Passage Home Begins”.. again this sounds very

dramatic, but for anyone knowing anything about ships would know we were

empty – the hull is well out of the water – look at the waterline. In

fact we were proceeding upstream to begin loading and the photo was

taken from the middle of the Pont de la Concorde and the bridge in the

picture is the Pont Alexandra III. |

| |

| We always arranged to arrive on a Friday and

on this first voyage, everything went according to plan. As I have

previously mentioned, we were met by Pan’ Paris agent Robert Mouzillat

who had arrange for us to moor alongside the floating Club House of the

Touring Club de France. So we were able to see the sights of Paris but

with little spending money it was mainly a ‘walkabout’ on this first

visit. We ‘dressed ship’ for the occasion and Robert and friends were

entertained on the fore deck. Later Aubrey Forshaw turned up having

flown over from London, interested to see the loading of the first

consignment on its way back to London. There were several times later on

when he travelled with us – he was a great Francophile. |

| |

|

|

Entertaining on the fore deck. |

| |

| On the Monday morning early, we cast off and

moved up river to the commercial docks, I think it was called Quay

Austerlitz and we loaded 250,000 books – the very first Pan titles –

printed by French printers who we learnt could not speak any English –

the French compositors setting the type in English. Quite an

achievement. |

| |

|

|

At the Quay d' Austerlitz in Paris

|

| |

| Loading took most of the day and on

completion, we dropped back down river to our previous berth ready for

an early departure the following morning. |

| |

|

|

Loading the boxes of books. |

| |

| We departed the next morning, a Monday early

in June 1947 – can’t remember the précis date after all these years –

and sailed downstream feeling well pleased with ourselves and knew much

more about the routine of passing through the locks. Maurice, our river

pilot (obligatory), always took the wheel which left the skipper and I

time to relax and enjoy the scenery. Our two young crewmen would be

washing down the decks and stowing away ropes, fenders etc ready for our

sea crossing. It was a straight forward run down river to Rouen where we

dropped our Pilot. The Seine at Rouen is tidal with a considerable rise

and fall and we quickly learnt that we needed to be aware of the ‘bore’

that creates such a back wash, at certain states of the tide. We

proceeded downstream to Le Havre with Skipper navigating and me at the

wheel and at times it was quite tricky, particularly when faced with an

oncoming French barge of some 2000 tons charging upstream. This first

trip was proving quite a ‘learning curve’ for us, as did the rest of the

voyage back to the UK. |

| |

| The Skipper and I had discussed the best

course to take when crossing the Channel. We had to be off Dungeness by

dawn to pick up our pilot who would take us round the coast as far as

Tilbury in the Thames Estuary and allowing for the tidal stream up and

down the Channel, I plotted our course for us to arrive off Dungeness

about 0800hrs. The weather was beautiful and the sea a flat calm but as

we approached the English coast, we were suddenly engulfed by a thick

sea mist which cut visibility to zero. We reduced speed to a crawl, and

using the foghorn, we crept on and navigating by dead-reckoning

proceeded very cautiously towards Dungeness. When I calculated we had

‘run our distance’ which should have put us about one mile off the shore

we stopped to listen and using our lead-line took soundings to establish

how near we were to the shore and our two crew were up on the bow as

lookouts. Within minutes we suddenly saw large white buildings about 500

yards ahead and we quickly turned away to follow the coast towards

Dungeness. By studying the chart, we were able to establish that what we

had seen was the seafront at Bexhill-on-Sea, some 30 miles West of

Dungeness. So my navigation skill, learnt while in the Navy, had been

put to the test and found wanting but Skipper didn’t blame me as he had

agreed with me the course we took crossing the Channel. So we made up

time and met the Pilot boat at Dungeness with a sigh of relief.

|

| |

| Passing Dover, the Pilot spotted a fishing

boat, suggested we go alongside and puzzled, we did as he suggested. The

skipper of the fishing boat tuned out to be his brother and coxswain of

the Dover Lifeboat. In exchange for a pack of duty free cigarettes, we

received a dozen mackerel and we all enjoyed a super breakfast !! |

| |

| Proceeding past the Goodwin Sands – always

tricky – round North Foreland and into the Thames Estuary we eventually

arrived off Tilbury to be met by a Customs launch, this being standard

procedure for all incoming vessels. We were asked where we had come from

and on replying “Paris”, they replied “Please proceed to Tilbury Landing

Stage and await for Customs inspection of your cargo”. This we did, two

Customs officers boarded us and immediately asked “where are these

‘dirty’ books from Paris” They had obviously had a tip off – Paris was

well known for producing pornography but the laugh was on us as we had

laid out for their inspection a copy of each of the ten titles we were

carrying............ titles by well known authors, such as Rudyard

Kipling, Agatha Christie, J B Priestley etc etc ................ and you

should have seen their faces which quickly turned to smiles and hand

shakes all round. A copy of each title was presented to them and were

told that they would be added to their library of reading material in

their rest room where they waited for ships to arrive. After that, every

subsequent trip, they just waved us through. |

| |

|

| |

|

Once in the Thames, ships come under the authority of the Port of London

Authority (PLA) and our London Office had arranged for us to be unloaded in

St. Katharine's Dock. Finding this particular Dock proved difficult as we

didn’t have large scale charts of the Thames showing all the Docks and their

Lock Gates where we would enter, so after various enquiries with other craft on

the river we eventually found the dock entrance where we passed through into St.

Katharine’s Dock . Here was our next experience, where I nearly caused a

dock strike ! Being directed to our berth, we were greeted by the sight of

two teams of dock workers waiting to unload us. Each team comprised 15

people plus a foreman. Bear in mind, these guys were used to dealing with

big cargo vessels and the rules stated exactly what each member of the team

would do.... work in the hold loading the cargo onto hoists, manhandling the

hoists up through the hatch to deck level, hand signalling the crane driver to

hoist the load over the side on to the dock side, moving the cargo into a

warehouse. I quickly realised that instead of the 15 men plus

foreman present in each team, because of our size, only 6 men would be needed at

each cargo hatch. A standoff ensued between me and the foreman about this,

who threatened, in no uncertain terms, he would call a strike, so were obliged

to watch 6 men work the cargo while the rest stood around smoking. A

costly experience for the office who later were able to come to an arrangement

with the PLA, that we could proceed upstream to Kingston upon Thames and do the

unloading ourselves.

Having unloaded, we proceeded upstream to Kingston, where we moored.

Thus ended our first eventful trip and shortly after the first ten titles

started to appear in bookshops around the country (and that’s another story) |

| |

| At one time my boss, Alan Bott, had let it be

known that he would appreciate a Camembert cheese, not being available

in the UK at that time which I had duly purchased in Rouen. After every

trip, I had to go to the London Office to collect the crew’s wages and

any instructions concerning our next trip. At the time there was a Green

Line Bus service from Kingston passing through London and terminating at

Hitchen, so this was a convenient and quick way to Hyde Park Corner and

Pan’s London Office at Headford Place. So after this first trip, I take

off by bus clutching the Camembert cheese placing it careful on the rack

above my seat. In my anxiety to get off at the right stop, I forget

about the cheese and arrive at the office and rather sheepishly have to

explain to the boss that his cheese was on its way to Hitchin. “Well

what are you going to do about it” I telephone the bus depot at Hitchin

to be told “Nothing has been handed in here – try catching the bus on

its return journey” I get back to Kingston, meet the bus, claim the

cheese, which due to the warmth of the bus was by this time smelling

distinctly high and the bus conductor’s parting comment as I got off the

bus “No wonder nobody sat in that part of the bus- the smell was awful

!! “ And the boss got his cheese. |

| |

| Let me conclude this saga by telling you of

various incidents that occurred during the two years we ran between

London and Paris until the day came when Pan could print in England,

which was obviously more satisfactory. |

| |

|

Between June 1947 and July 1949, we would have made one trip every two weeks and

the routine was largely the same each time and we became quite well known on the

Thames and Seine. At that time the Port of London was an extremely busy

port – remember this was long before ‘containerisation’ of cargos – and cargo

ships of all sizes would be moving up an down the Thames all the time, so it was

‘scary’ at times for us but we managed. Our skipper was very

experienced from his days as a trawler skipper and we very quickly learnt how to

navigate down the Thames, Down past the large Ford works at Dagenham and Tate &

Lyle’s riverside refinery at, I think, Purfleet, where the river was much wider

and then on past Tilbury, where we picked up our Pilot to take us round to

Dungeness, it was straightforward and not so ‘tense’ (get the picture ?).

The locks on the Seine, where we had Maurice our river pilot to negotiate for

us, we usually found we could get to Paris in under 48 hours, which gave us some

free time in Paris, before loading. The occasional gales in the Channel

would delay us but most times an ‘round trip’ would be 12/14 days.

|

| |

|

|

Hammersmith Bridge |

| |

|

The Thames is tidal as far as Teddington,

and great care had to be taken when ‘shooting the bridges’ and Hammersmith

Bridge was always a ‘tricky’ one as it had quite a low span. On one trip we

misjudged the height of the tide and realised at the very last minute we were

not going to get underneath. I remember, I was at the wheel at the time and we

always approached this particular bridge dead slow, so I was able to reverse

away and the skipper decided to lay alongside a nearby quay to wait for the tide

to turn. Unfortunately we lay alongside too long and got caught on the mud All

in a days work !

|

| |

.jpeg) |

| |

.jpeg) |

|

In the mud at Hammersmith. |

| |

| While in Paris, as I mentioned earlier, we

were fortunate to be able to moor alongside the floating club house of

the Touring Club de France (TCF) which lay just upstream from the Pont

de la Concorde, usually arriving late Friday afternoon, giving us a

couple of free days before proceeding upstream to the commercial dock at

Quay Austerlitz to load. Aubrey Forshaw (ADF) was a great Francophile

and love to slip over to Paris when we were there. One time he decided

to hold a drinks party on board for several authors who happened to be

in Paris – I think there might have been some literary event on at the

time. So we ‘dressed ship’, set out a drinks table and I suppose we must

have about twenty people aboard but the only one I can remember now was

J B Priestley. Pan had recently published his ‘Three Time Plays’ and as

it happened I had a copy. Thinking I might get him to sign my copy, I

approached the great man, who had settled himself in a chair on the

after deck, away from the main crowd, and was enjoying a quite moment

with a large whisky. I asked very politely if he would sign my copy and

was very rudely told to “F..........off, I never do signings”. I

realised he had had more than one whisky ! |

| |

|

| |

| ADF was always very generous on these

occasions, and I remember he took me to one of his favourite

restaurants, where he was greeted by the maitre’d who obviously knew him

from previous visits. After the usual c’a va’s and merci beaucoups we

were handed each a pair of binoculars and referred to a large menu board

at the other end of the restaurant, which was long and narrow with

cubicles down each side to sit four. The menu board was so far away that

you needed binos to read it. ADF was a great raconteur, very keen on

motor racing and in particular old Bentleys, which he restored. He and a

friend raced Austin Healey’s at Silverstone club meetings and I would go

along to lap score. He became a father-figure to me over the years, was

at my wedding and was later referee for my two adopted children. |

| |

| I have digressed. Sundays in Paris was always

a time to relax and my favourite walk after a late breakfast, was up the

Champs-Elysees as far as the Arc de Triomphe and back and then a stroll

across the Pont de la Concorde to look down over the parapet on 'Laloun'

This was a time when Paris had regular confrontations between the

gendarmes and Communist supporters and one summer Sunday morning, I was

standing on the bridge when I realised that on one side there was a mass

march with banners and on the other side massed ranks of riot police and

I was in the middle. As each side approached, I quickly realised there

was going to be a battle so I dashed towards the police shouting “Anglais

– Anglais” and waving my passport. In my school boy French, I explained

who I was and was let through the police ranks, much to my relief. |

| |

|

Now I must confess to a little smuggling to give us some spending money

while in Paris. We always had fenders over both sides of the ship to

protect the hull when passing through the many locks on the Seine and the lock

at Teddington when going up river to Kingston upon Thames. We used old

motor tyres wrapped around with canvas and rope. We learnt early on that

car tyres were in short supply in France so we would purchase retreads in the

UK, use them as fenders and then sell them to Parisian motorists. I think

at first, Robert Mouzillat had the first set, told his friends and we soon were

doing a roaring trade but after a while it was beginning to get out of hand so

we stopped before we got into trouble with Customs who would be sharp enough to

notice that we would be going out with twelve fenders on each side but coming

back with only six. |

| |

| We usually went out empty but after awhile

the London office negotiated a deal with the Foreign Office for us to

ship over to their Paris Embassy, various supplies and that helped

towards running costs. |

| |

|

By 1949, paper for printing was becoming more available in the UK and

the decision was taken to sell 'Laloun' and use UK printers. Skipper

Saunders went back to deep sea trawlers, our young crewmen moved on and at an

interview with ADF I was asked what I was going to do. ADF knew I had gone

into the Navy straight from school and then joined Laloun after being demobbed.

So he said, I can remember this even today...” Take some leave and come back and

see me in 10 days time” Which I did

and he said “ We have decided to make you Export Sales

Manager”.......... and of course there were no export sales at that

time. (but that is another story) |

| |

|

| |

| To be continued ....... |

| |

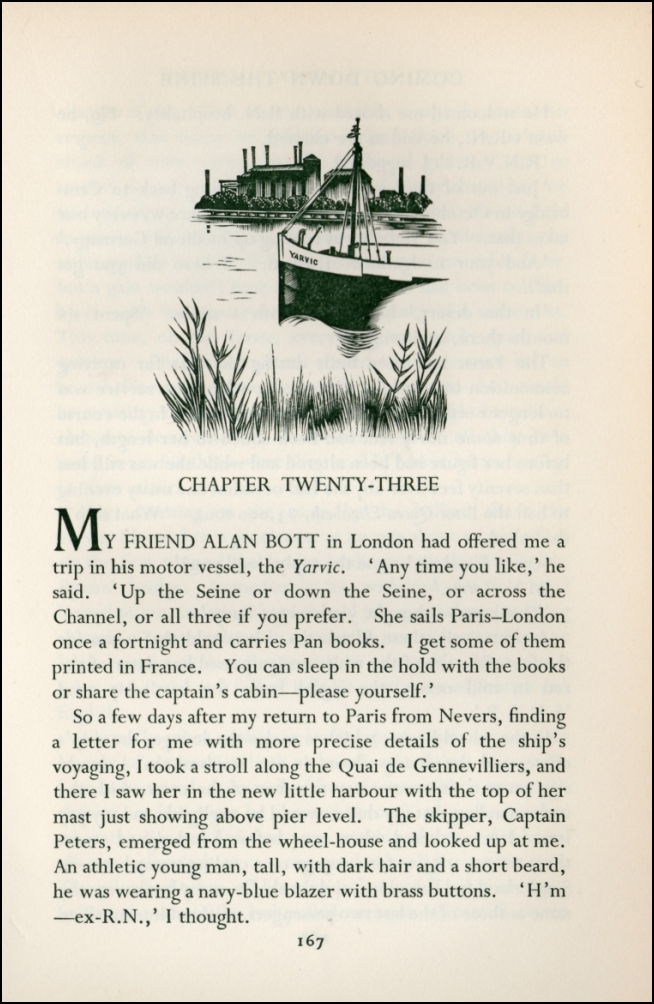

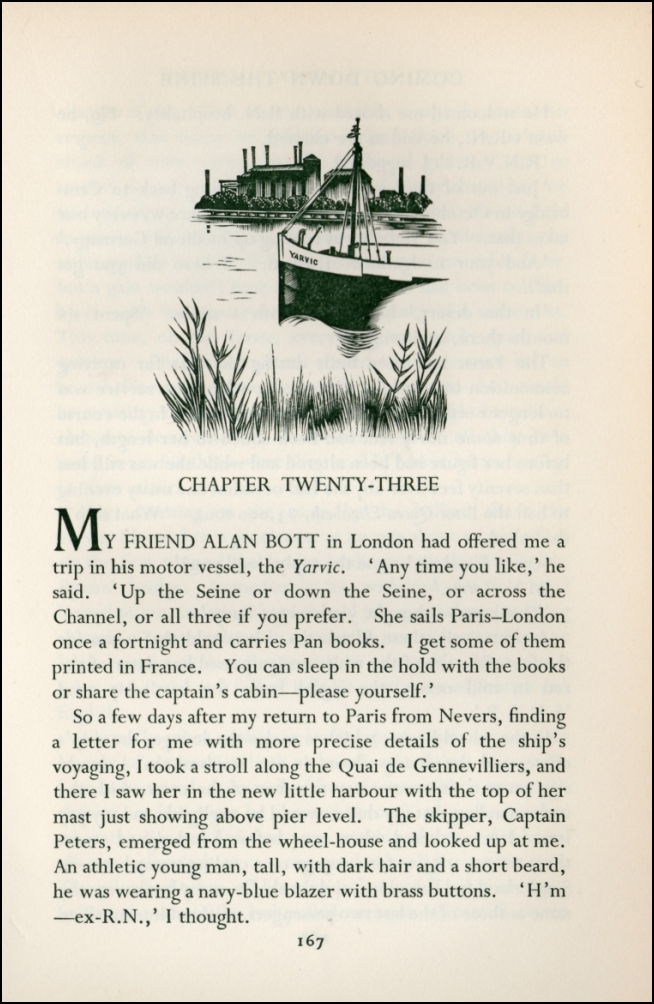

| The 'Laloun'

was later replaced by the 'Yarvic' |

| |

|

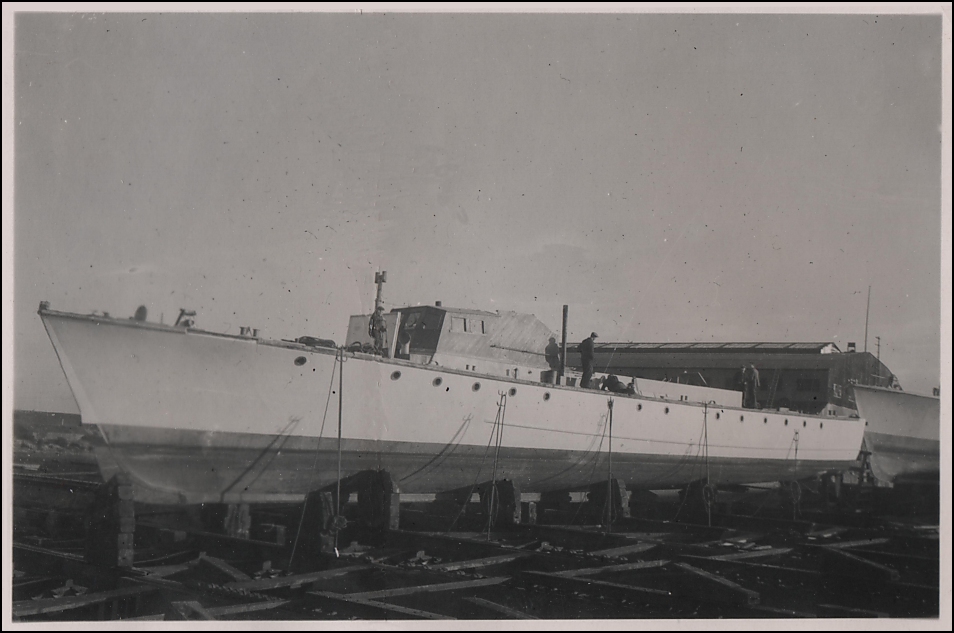

| The 'Yarvic' was built by Dunston's at

Thorne in 1944, and scrapped in France in 1967 |

| |

| As regards your ‘Yarvic’ story it is an

interesting photo as it shows her lying on the mud, obviously tidal so

cannot be on the Seine. I suspect the photo was taken down the Thames

estuary somewhere, up some creek around the Medway area. I would be

interested to hear more about the Book and whether the author took up

Alan Bott’s offer? |

| |

|

| From the

book “Coming Down The Seine’ by Robert Gibbings |

| |

| The ‘Yarvic’ was a wartime built replica of

the Clyde Puffers of pre-war days and the Admiralty built about 50 of

these to serve the fleet at its various anchorages. They were all given

numbers after the prefix VIC short for ‘Victualing Inshore Craft’. Most

were disposed of at the end of the war and some were purchased for

coastal cargo work which ‘Yarvic’ was, probably owned by the skipper.

She was chartered by Pan, as Laloun was not really a paying proposition

as she was expensive to run and I suppose there were contracts to

complete with the French printers. There was also an arrangement with

the Foreign Office to convey supplies to the British Embassy in Paris.

As I think I told you, 'Laloun' was sold in 1949 to a consortium and was

used to carry duty frees from North Africa to the South of

France/Northern Italy (in other words ‘smuggling’ ) and was eventually

caught. The story is told in Nicholas Montsarrat’s book ‘The Ship That

Died Of Shame’ Interestling, there are one or two VIC’s still surviving

– VIC32 is owner skippered running short holiday cruises off the West

Coast of Scotland and some years ago I had a cruise on her from

Inverness to Fort William through the Caledonian Canal. I know of one

other, now derelict lying at Inverary and used in the ‘Para Handy films,

her name was ‘Maggiie’ |

| |

|

.jpeg)

.jpeg)